米国 (Beikoku) is an older name for the United States in Japanese.

But the origins of 米国 — and the reason it ended up being the “official” name of America in Japanese and not Chinese — is a bit complicated. For starters, it has nothing to do with the original meaning of 米, much like how the origins of the present-day Chinese word for the US (美国, Meiguo) has little to do with the original meaning of the character 美 (“beautiful”) — contrary to popular belief.

It’s just that when Japan first came into contact with Americans from the Perry Expedition, “America” was transliterated into Japanese as 米利幹 (meriken, メリケン).

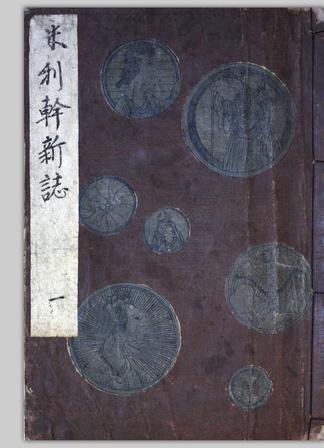

Meriken shinshi (米利幹新誌), written circa 1855, is probably the first printed Japanese book about America.

Over time, the US came to be known in Japanese in many other names, such as 亜米利加 (Amerika) and 北米合衆国 (Hokubei Gasshūkoku), all of which evolved into 米国.

In nearby China, where the US from the very beginning was known to some as 花旗国 (Huāqíguó, literally “flowery flag country”), a missionary-run Chinese-language magazine (Eastern Western Monthly Magazine) tried to translate the full name, “United States of America,” into Chinese, and ended up with 亚美利加兼合国 (Yà měi lìjiā jiān hé guó, literally “America United State”).

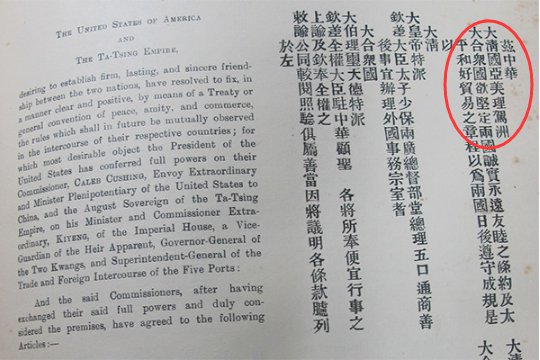

This was the first documented literal Chinese translation of “USA,” and it appeared sometime around the 1830s, when the magazine was active. The 1844 Treaty of Wangxia, the first diplomatic agreement between the US and any Chinese government, had the US written in the Chinese text as 亚美理驾洲大合众国 (Yà měi lǐ jià zhōu dà hézhòngguó).

“亚美理驾洲大合众国” as it appears in the Chinese version of the Treaty of Wangxia

Despite the treaty, the Chinese name for the United States was not set in stone. In 1848, a few years after the Treaty of Wangxia was signed and a few years before the Perry Expedition to Japan (in 1853), a Chinese geographer named Xu Jiyu (徐继畬), who had a history of coming into contact with foreigners, wrote a book about the outside world, in which he referred to the United States as 米利坚合众国 (Mǐlì jiān hézhòngguó), or 米利坚 (Mǐlì jiān) for short.

This is perhaps the closest relative to the modern Chinese translation of America’s full name, 美利坚合众国 (Měilìjiān hézhòngguó), the only difference being that the character 米 — which happens to also be the same character that the Japanese would use for America — is used, not 美, presumably because Xu believed 米 (Mǐ) is a better transliteration of “America” than 美 (Měi).

It’s possible that somehow, Xu Jiyu’s 米利坚 spread to Japan and inspired the first Japanese translation of America, 米利幹. In any case, Qing China, not Japan, is where the character 米 was first used to refer to the United States of America.

But unlike Japan, where people were apparently only exposed to variants of 米利坚 which resulted in 米国 becoming part of the Japanese lexicon, 米利坚 did not stick in China, which had already signed a treaty using a name of America that had the character 美 in it, instead of 米.

As the Qing Dynasty continued its decline, the Chinese upper classes started reading up on literature on revolutions overseas — including the American Revolution — that referred to the United States as 美利坚 or 美国. This effectively established 美国 as the Chinese name for America for good.

Presently, 米国 is an archaic term across the East Asian cultural sphere. It’s still used in Japan, but not as much compared to アメリカ (a me ri ka), which is derived from 亜米利加.

Korean is an interesting case, as the United States is written in alphabetical Hangul as 미국 (migug), which may be written in characters as 美国 or 米国. In South Korea, the Hanja equivalent of 미국 is 美国, whereas North Korea prefers the old school equivalent of 米国, which was probably the standard in Korea when it was under Japanese rule.

The “oddball” appears to be Vietnamese, which has clung on to the 18th century Chinese name for the US, 花旗 (Hoa Kỳ). Though Mỹ (美) is sometimes used as well.