Ok, I’ll try to unpack this as best as I can but please bear in mind that we are talking about 5,000 years of human history here, so this is going to be a very abridged history, or we could be here for weeks, so my apologies if I skip over anything important

Firstly, what we think of as “China” is actually a fairly modern concept relatively speaking, and for most of its history, China was a mish-mash of different states, factions, tribes and ethnic groups all vying for power and control

There were periods of peace under Emperors such as 秦始皇 Qín Shǐ Huáng, who managed to unify what is now “China”, only for factions to break away again violently

One of the most formative times in China’s history is literally called, “The Warring States Period”, which gives you an idea of how things were

This independent and fractious nature of early to mid-era China is easily visible in the language map of Modern China, which is in itself a hodge-podge of different languages and dialects which have evolved over time from various different ethnic and tribal groups that occupied the various states and provinces we now call “China”

/

/

The Origins of “Mandarin”

Mandarin grew out of the dialects of Northern China, specifically the dialect spoken around Běijīng (formerly Peking), and while this isn’t a perfect analogy, it is the Chinese equivalent of British Received Pronunciation

That is to say it was the language used by the wealthy and educated elites in Běijīng, who wielded the political power and control over China, and so Mandarin became the language of power and influence in China

Since the Communist Revolution in China, the language of Mandarin has been called 普通话 pǔtōnɡhuà or “The Common Tongue”, in an attempt to sever these old imperial connotations and make the language seem more egalitarian and, well “Communist”

However it’s former name 官话 guānhuà or “The Language of The Officials”, betrays it’s more elitist origins

Just like Received Pronunciation in Britain, 普通话 pǔtōnɡhuà is considered the “correct” form of Chinese, and is the form of Chinese taught in schools, and used on television and radio news broadcasts

It would be very odd to turn on BBC News in the UK and hear the news anchor open with:

“Wha’gwan rudeboi,

Dere was bare scenes in London today fam, as hella man get shank, dem Babylon still no catch da raasclaat”

Now while I’d definitely watch more news if we had an MLE/Patois speaking anchor, the BBC still insist on Received Pronunciation for their news anchors, as it is considered the most accessible and understandable dialect of English, even if it isn’t widely spoken outside of a small pocket of Southern England

The same is true in China, and 普通话 pǔtōnɡhuà remains the language of politics and news broadcasts, even if the average Chinese person in the street may speak a far more colloquial dialect of Chinese

Indeed, China is so large and populous, that individual cities often have their own unique dialect of idioms, slang and colloquialisms, that can make it seem like a different language entirely, when really it’s just a hyper localised and colloquial dialect of Mandarin

/

/

So Why Do We Call It Mandarin?

Mandarin went on a long linguistic journey to arrive in the English language, but it essentially refers to a bureaucratic scholar who aided the government, while not perfect, a modern analogy would be a civil servant

In China, these “Mandarin” were called 官 guān or “officials”, the same origin as the original name of Mandarin Chinese, 官话 guānhuà or “The Language of The Officials”

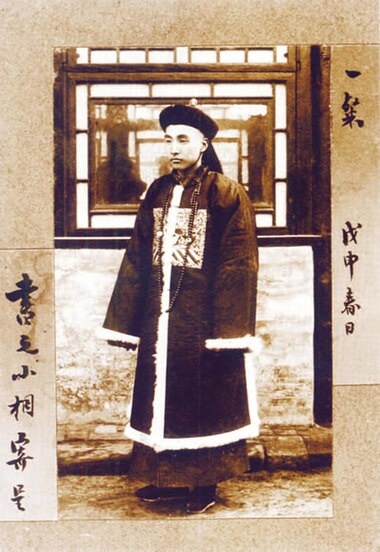

A “Mandarin” or 官 guān , date unknown (pre-1911)

China had several periods of political isolation, where it closed its borders and refused any international trade

One such period was the 清朝 Qīngcháo, or Qing Dynasty (c.1640 to 1912), where China opened just one single port for all international trade, the port of Canton, which is now known as 广州 Guǎngzhōu

The Port of Canton is the origin name of the other major Chinese language, Cantonese

China was extremely protective of Canton and was very selective on who they would and wouldn’t trade with, and would only trade via government sanctioned merchants

This led to a trade imbalance and the beginning of a bitter trade war between Britain and China that led Britain to flood China with opium, leading to the Opium Wars

This isolationism and trade hostility meant that Britain had to funnel much of its trade via the Portuguese enclave on Macau, southwest of the port of Canton/Guǎngzhōu on the Pearl River estuary

Portugal had a presence on Macau since 1557, and remained there as recently as 1999

If you visit Macau today, you will still find it a fascinating mix of Chinese, Iberian and British influences

As Britain was trading with this Portuguese enclave from the early 1600s onwards, Britain adopted many of its Chinese terms from the Portuguese, including this word Mandarin for the Chinese bureaucrats

Mandarin is actually a corruption of the Portuguese word “Mandarim”, which they borrowed and corrupted from the Malay word “Menteri”, which they borrowed from the Sanskrit language “Mantrī”

Regardless whether it was Mandarin, Mandarim, Menteri or Mantrī, the meaning was always the same, a “counsellor or advisor”

As European traders, especially British traders, had come to call these government officials “Mandarins”, the governmental language they spoke also became known as Mandarin Chinese, the form of Chinese spoken by these Mandarins

In a rather delicious piece of book-ending, that is the exact same origin as the old Chinese word for the language, 官话 guānhuà or “The Language of The Officials”