Because China’s terrain is hilly, especially in South China, the transportation in ancient times was very inconvenient, and it was also inconvenient to communicate in person. We could only communicate by letter, which led to many dialects.

Dialectologist Jerry Norman estimated that there are hundreds of mutually unintelligible varieties of Chinese. These varieties form a dialect continuum, in which differences in speech generally become more pronounced as distances increase, although there are also some sharp boundaries.

These varieties form a dialect continuum, in which differences in speech generally become more pronounced as distances increase, though the rate of change varies immensely. Generally, mountainous South China exhibits more linguistic diversity than the North China Plain.

In parts of South China, a major city’s dialect may only be marginally intelligible to close neighbors.

For instance, Wuzhou is about 190 kilometres (120 mi) upstream from Guangzhou, but the Yue variety spoken there is more like that of Guangzhou than is that of Taishan, 95 kilometres (60 mi) southwest of Guangzhou and separated from it by several rivers.

In parts of Fujian the speech of neighboring counties or even villages may be mutually unintelligible.

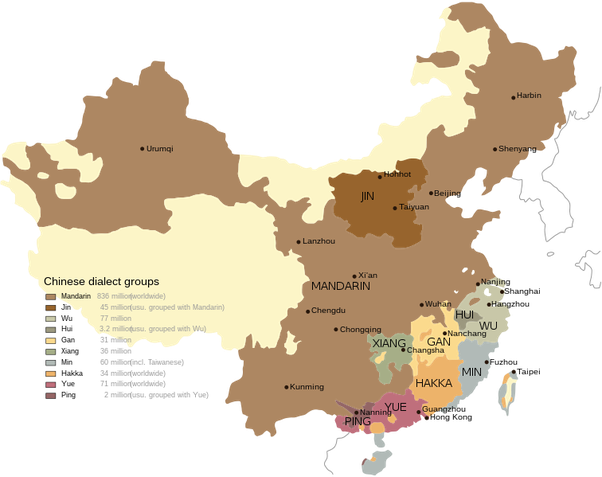

Dialect groups

- Mandarin (65.7%)

- Min (6.2%)

- Wu (6.1%)

- Yue (5.6%)

- Jin (5.2%)

- Gan (3.9%)

- Hakka (3.5%)

- Xiang (3.0%)

- Huizhou (0.3%)

- Pinghua, others (0.6%)

The conventionally accepted set of seven dialect groups first appeared in the second edition of Yuan Jiahua’s dialectology handbook (1961):

Mandarin

This is the group spoken in northern and southwestern China and has by far the most speakers. This group includes the Beijing dialect, which forms the basis for Standard Chinese, called Putonghua or Guoyu in Chinese, and often also translated as “Mandarin” or simply “Chinese”. In addition, the Dungan language of Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan is a Mandarin variety written in the Cyrillic script.

Wu

These varieties are spoken in Shanghai, most of Zhejiang and the southern parts of Jiangsu and Anhui. The group comprises hundreds of distinct spoken forms, many of which are not mutually intelligible. The Suzhou dialect is usually taken as representative, because Shanghainese features several atypical innovations. Wu varieties are distinguished by their retention of voiced or murmured obstruent initials (stops, affricates and fricatives).

Gan

These varieties are spoken in Jiangxi and neighbouring areas. The Nanchang dialect is taken as representative. In the past, Gan was viewed as closely related to Hakka because of the way Middle Chinese voiced initials became voiceless aspirated initials as in Hakka, and were hence called by the umbrella term “Hakka–Gan dialects”.

Xiang

The Xiang varieties are spoken in Hunan and southern Hubei. The New Xiang varieties, represented by the Changsha dialect, have been significantly influenced by Southwest Mandarin, whereas Old Xiang varieties, represented by the Shuangfeng dialect, retain features such as voiced initials.

Min

These varieties originated in the mountainous terrain of Fujian and eastern Guangdong, and form the only branch of Chinese that cannot be directly derived from Middle Chinese. It is also the most diverse, with many of the varieties used in neighbouring counties—and, in the mountains of western Fujian, even in adjacent villages—being mutually unintelligible. Early classifications divided Min into Northern and Southern subgroups, but a survey in the early 1960s found that the primary split was between inland and coastal groups. Varieties from the coastal region around Xiamen have spread to Southeast Asia, where they are known as Hokkien (named from a dialectical pronunciation of “Fujian”), and Taiwan, where they are known as Taiwanese. Other offshoots of Min are found in Hainan and the Leizhou Peninsula, with smaller communities throughout southern China.

Hakka

The Hakka (literally “guest families”) are a group of Han Chinese living in the hills of northeastern Guangdong, southwestern Fujian and many other parts of southern China, as well as Taiwan and parts of Southeast Asia such as Singapore, Malaysia and Indonesia. The Meixian dialect is the prestige form. Most Hakka varieties retain the full complement of nasal endings, -m -n -ŋ and stop endings -p -t -k, though there is a tendency for Middle Chinese velar codas -ŋ and -k to yield dental codas -n and -t after front vowels.

Yue

These varieties are spoken in Guangdong, Guangxi, Hong Kong and Macau, and have been carried by immigrants to Southeast Asia and many other parts of the world. The prestige variety and by far most commonly spoken variety is Cantonese, from the city of Guangzhou (historically called “Canton”), which is also the native language of the majority in Hong Kong and Macau. Taishanese, from the coastal area of Jiangmen southwest of Guangzhou, was historically the most common Yue variety among overseas communities in the West until the late 20th century. Not all Yue varieties are mutually intelligible. Most Yue varieties retain the full complement of Middle Chinese word-final consonants (/p/, /t/, /k/, /m/, /n/ and /ŋ/) and have rich inventories of tones.

The Language Atlas of China (1987) follows a classification of Li Rong, distinguishing three further groups:

Jin

These varieties, spoken in Shanxi and adjacent areas, were formerly included in Mandarin. They are distinguished by their retention of the Middle Chinese entering tone category.

Huizhou

The Hui dialects, spoken in southern Anhui, share different features with Wu, Gan and Mandarin, making them difficult to classify. Earlier scholars had assigned to them one or other of these groups, or to a group of their own.

Pinghua

These varieties are descended from the speech of the earliest Chinese migrants to Guangxi, predating the later influx of Yue and Southwest Mandarin speakers. Some linguists treat them as a mixture of Yue and Xiang.

Some varieties remain unclassified, including the Danzhou dialect of northwestern Hainan, Waxiang, spoken in a small strip of land in western Hunan, and Shaozhou Tuhua, spoken in the border regions of Guangdong, Hunan, and Guangxi. This region is an area of great linguistic diversity but has not yet been conclusively described.

Most of the vocabulary of the Bai language of Yunnan appears to be related to Chinese words, though many are clearly loans from the last few centuries. Some scholars have suggested that it represents a very early branching from Chinese, while others argue that it is a more distantly related Sino-Tibetan language overlaid with two millennia of loans.