It depends on your original native language.

I assume you are a native English speaker since the question was in English.

If you study full time using an immersion system you can be almost fluent in 12 months if you learn Spanish.

To do the same thing with Mandarin will take about 3 to 5 years.

The Sino-Tibetan Language Family

Description of the Sino-Tibetan Language Family Sino-Tibetan (ST) is one of the largest language families in the world, with more first-language speakers than even Indo-European. The more than 1.1 billion speakers of Sinitic (the Chinese dialects) constitute the world’s largest speech community. ST includes both the Sinitic and the Tibeto-Burman languages. Most scholars in China today take an even broader view of ST (called Hàn-Zàng in Mandarin), including not only these two branches, but Tai (= “Daic”) and Hmong-Mien (= Miao-Yao) as well. Even taking ST in its narrower sense, we are dealing with a highly differentiated language family of formidable scope, complexity, and time-depth. Tibeto-Burman (TB) comprises hundreds of languages besides Tibetan and Burmese, spread over a vast geographical area (China, India, the Himalayan region, peninsular SE Asia). The Proto-Sino-Tibetan (PST) homeland seems to have been somewhere on the Himalayan plateau, where the great rivers of East and Southeast Asia (including the Yellow, Yangtze, Mekong, Brahmaputra, Salween, and Irrawaddy) have their source. The time of hypothetical ST unity, when the Proto-Han (= Proto-Chinese) and Proto-Tibeto-Burman (PTB) peoples formed a relatively undifferentiated linguistic community, must have been at least as remote as the Proto-Indo-European period, perhaps around 4000 B.C. The TB peoples slowly fanned outward along these river valleys, but only in the middle of the first millennium A.D. did they penetrate into peninsular Southeast Asia, where speakers of Austronesian (=Malayo-Polynesian) and Mon-Khmer (Austroasiatic) languages had already established themselves by prehistoric times. The Tai peoples began filtering down from the north at about the same time as the TB’s. The most recent arrivals to the area south of China have been the Hmong-Mien (Miao-Yao), most of whom still live in China itself. The field of ST linguistics is only about 50 years old, and has been a flourishing object of inquiry for only the past 25. Scholars have been trying since the mid-19th century to situate Chinese in a wider genetic context. As the relationships between Chinese and Tibetan on the one hand, and Tibetan and Burmese on the other became obvious, vague notions of an “Indo-Chinese” family (Hodgson 1853, Conrady 1896) began to crystallize. The term Sino-Tibetan seems to have been used first by R. Shafer (1939-41, 1966/67), who conceived of it as a tripartite linguistic stock comprising Chinese, Tibeto-Burman (TB), and Tai (= “Daic”). Much of the area in which TB languages are spoken is still virtually inaccessible for linguistic fieldwork, at least by foreign scholars (NE India, Burma, Yunnan, Sichuan, Tibet, Laos, Vietnam). Only in Thailand and Nepal has vigorous international fieldwork been carried on since the 1960’s. By any criterion (number of speakers, antiquity of documented written history, cultural significance, influence on other languages) Chinese ranks as one of the most impor

https://stedt.berkeley.edu/about-st.html

Lynch, Indo-European Language Family Tree

The Indo-European Language Family Tree By Jack Lynch , Rutgers University — Newark Note: This is the newest version (2023) of my language tree: it’s more extensive and better laid out than the old one. A PDF version is also available; it looks better when printed. If you’re interested in the older one, the image appears below. The chart below shows the relations among some of the languages in the Indo-European family. Though you wouldn’t think to look at the tangle of lines and arrows, the chart is very much simplified: many languages and even whole language families are left out. Use it, therefore, with caution. The coverage is most thorough, but still far from complete, in the Germanic branch, which includes English. A key: Black type is used for living languages; gray type represents “dead” ones — that is, languages with no native speakers. I use boldface type for languages with more than 10 million speakers today, and larger boldface for those with more than 100 million. The dashed lines from Old Norse to Old English and from French to Middle English represent not direct descent, but the influx of vocabulary following the “Viking” and Norman Invasions. Some caveats: The diagram is English-centric — not because English has any unique place in the Indo-European family, but because it’s the subject I teach. I’ve grossly oversimplified everywhere. In the interest of readability, I’ve left out dozens of languages, including the entire Tocharian and Dacian families, the Plattdeutsch languages, and so on. There are somewhere between 400 and 500 living Indo-European languages, and scrillions of dead ones, and I can’t cover them all. The historical phases of many languages — Old Swedish, Middle Swedish, Modern Swedish — have been left out. Although each lineage is arranged chronologically, from top to bottom, you can’t compare branches for historical sequence. Albanian, way up near the top, is still spoken today; Middle English, way down near the bottom, hasn’t been spoken in half a millennium. The branches aren’t arranged according to geography or similarity between languages, so you can’t assume German and Hindi are closely related, or that Welsh speakers have lived close to Hittite speakers. Avestan is close to Slavic only because they fit on the page that way. The dotted lines show the two most important sources of large amounts of English vocabulary from outside the main West Germanic inheritance. In real life languages are always exchanging words with other languages — Celtic words borrowed into Latin, Gaulish Frankish words picked up in Old French — and English has borrowed words from almost every language on this chart. You’ll have to imagine the spiderweb of dotted lines from almost every language to almost every other, because there’s no way to do it on a diagram like this. I try not to take sides in disputes over language evolution, but when I have to choose one of several competing interpretations or names for a language family, I generall

http://www.jacklynch.net/language.html

The reason is that you can transfer a lot of knowledge from English to Spanish because they both came from an original language that was similar and on top of that English borrows a lot of words from Latin.

Mandarin is basically 100% different. If you speak Thai or one of the other SEA languages that share similarities with Chinese then it may be the other way around. It really depends on how different the languages are now and if you have been exposed to at least some English from a young age (fairly common).

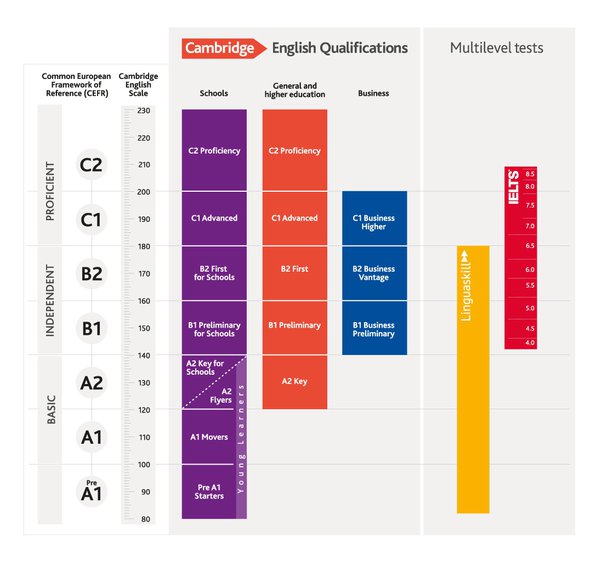

Fluent is generally measured using a scale like the “Common European Framework of Reference for Languages”.

Generally, people are called “fluent” around the border C1 of C2.

HSK6 is roughly at the bottom of C1 which is why they have recently added more levels.