The reason is that sound changes reduces the complex consonant clusters of Old Chinese and deleted final consonants over time. Old Chinese typically had short monosyllabic words with coda consonants, much like most of the native Germanic vocabulary of English (e.g., words like pink, strike, screw, sleep, dream, wink, wing, back, bend, first, sixth).

In most Chinese varieties today, none of these words have coda consonants or clusters:

As all of these consonants dropped off, tones evolved because the contours left over from the consonants remained, but even with tones, dozens of homophones developed out of any monosyllable.

Crosslinguistically, this is bizarre from the perspective of Indo-European, Afro-Asiatic, Niger-Congo, Pama-Nyungan, or Austronesian languages. Typically languages avoid homophones, and sound changes that would create homophones are often skipped. Additionally, languages with smaller consonant inventories and fewer clusters evolve to have longer words.

Linguists generally think homophone avoidance (or the tendency to avoid sound changes that result in homophones) is universal, and recently, Trott and Bergen (2020) went as far as testing the theory of homophone avoidance using AI models to test homophone avoidance. Their AIs produce similar levels of homophones in their artificial languages as human languages—therefore homophone avoidance.

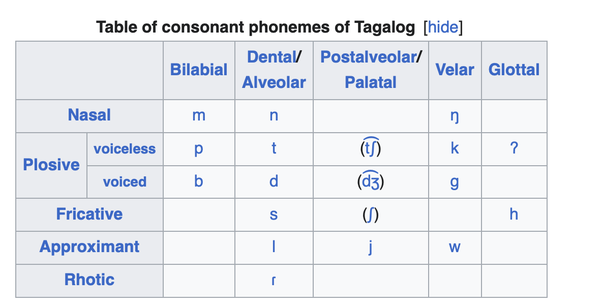

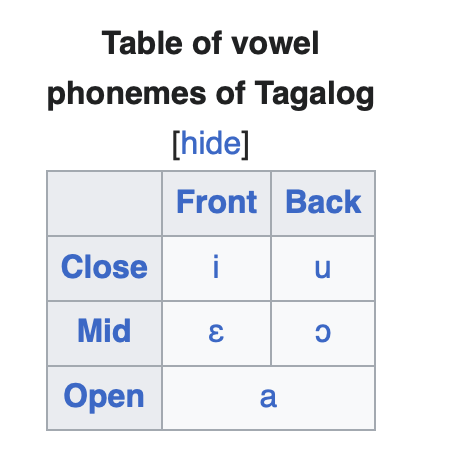

One Austronesian language, Tagalog, perfectly fits as a language homophone avoidance would predict. It has a consonant inventory even smaller than Mandarin’s, three vowels in native words, five vowels in Spanish and English loans, and no phonemic lexical tonal contrasts:

Yet, Tagalog doesn’t have more homophones than English. The simple reason is that it has almost zero monosyllabic words at all. No Tagalog sound changes have clipped off the ends of words. If you casually leaf through the Tagalog Swadesh list, you will see only four words or morphological forms that are monosyllabic out of 200:

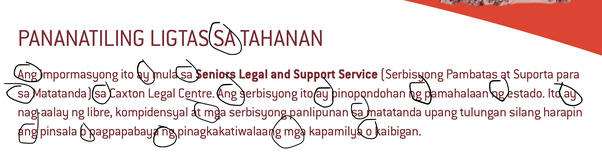

They are the second person singular ‘you’ in the absolutive case ka, the preposition sa, and the conjunction at which means ‘and,’ and another conjunction kung which means ‘if.’ That’s it! The core vocabulary of Tagalog is only 2% monosyllabic.

Outside of this core vocabulary, the only words of Tagalog I know that are monosyllabic are some of the pronouns in the ergative case, second person singular mo and first person singular ko, and a few clitics like the question marker ba, and din/rin which means ‘also,’ and the absolutive case marker ang, and ergative case marker ng. If you look at a block of Tagalog text, you’ll frequently see paragraphs without a single monosyllabic word besides the very important case markers ang/ng and the preposition sa, the preposition o, and the inverter ay (used whenever a sentence is not the default Verb-ergative-absolutive word order).

All of the nouns and verbs are at least two syllables. I can’t think of single noun in Tagalog that’s monosyllabic, and the only verb is an edge case, copular may which means ‘there is.’

It’s a bit of a simplification to say Chinese mostly has monosyllabic words. The stems are monosyllabic, but most Chinese words are used in compounds, where often two nouns with similar meaning are stuck together. Sampson (2013) argues that because Chinese has to reduce homophones by compounding nouns, homophone avoidance is not universal or even a sound theoretical concept.

I wouldn’t go that far. If 99% of the world’s languages follow homophone avoidance, I don’t think we should throw out the whole theory just because Chinese doesn’t. It is an interesting question why Chinese had sound changes that created so many homophones though, and I really wonder why. We understand the individual sound changes that created the homophones, but why this happened is a mystery.

References:

Sampson, G. (2013). A counterexample to homophony avoidance. Diachronica, 30(4), 579-591.

https://www.grsampson.net/ACth.pdf

Li, P., & Yip, M. C. (1998). Context effects and the processing of spoken homophones. Reading and Writing, 10, 223-243.

https://blclab.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/rw98.pdf

Trott, S., & Bergen, B. (2020). Why do human languages have homophones?. Cognition, 205, 104449.

https://pages.ucsd.edu/~bkbergen/papers/trott_bergen_2020.pdf