I do not see strong-enough evidence that it was the contributor, or even the dominant contributor.

Supporters of the “character simplification raised literacy rates” theory usually point to the timeline of China’s literacy levels rising in tandem with the implementation of Simplified Characters as the standard form. What they conveniently choose to ignore are the larger factors that led to raised literacy rates, and in particular, during which specific period in the last 60-odd years since the official promulgation of Simplified Characters as standard in Mainland China.

Let me first start by stating that I will not use Hong Kong and Taiwan, and their continued use of Traditional Characters, as cases-in-point here. Firstly, that line of argument has been used many times elsewhere – to repeat it here will be pointless, and only invite further polemical arguments leading nowhere. Secondly, we know that the Mainland, Hong Kong and Taiwan all had different historical backgrounds and hence, starting points — insofar as Chinese character usage, education and literacy were concerned.

Quoting the following paper: “Analysis on the Duration of Compulsory Education in China: A Study on the Necessity and Urgency of 12-year Compulsory Education” by Siyuan Su (2022):

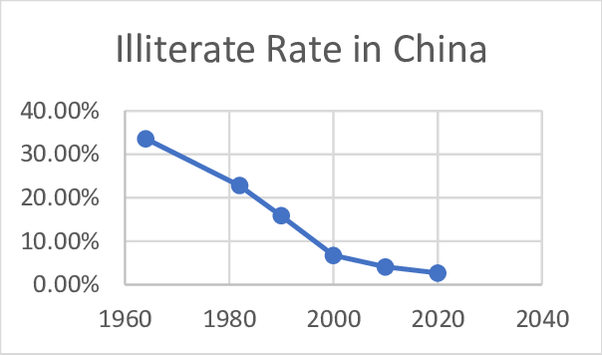

“According to China’s national census data, the illiterate rate in 1964 was 33.58%, and in 2020, the illiterate rate was only 2.67% (Figure 1). The illiterate rate has fallen sharply every year since the implementation of the 9-year compulsory education law. It can be clearly seen from Figure 1 that since the nine-year compulsory education was formally implemented in 1986, the illiterate rate dropped by 9.16% from 1990 to 2000.

After the implementation of the nine-year compulsory education in 1986, the illiterate rate has dropped significantly. The results of the fourth census released in 1990 and the fifth census released in 2000 showed that the illiterate rate dropped by 9.16% in 10 years. The 2020 census shows that the illiterate rate is only 2.67%. At the same time, nine-year compulsory education has been fully covered. The sharp drop in the illiterate rate has an inseparable relationship with the full implementation and development of nine-year compulsory education.”

Figure 1: Illiterate Rate of China

In other words, the fastest rate of decrease in illiteracy occurred from the mid-1980’s until the turn of the new millennium, post-dating the promulgation of Simplified Characters by at least two (2) decades. And that period of fastest progress coincided with a reform in education policies, specifically nine-year compulsory education.

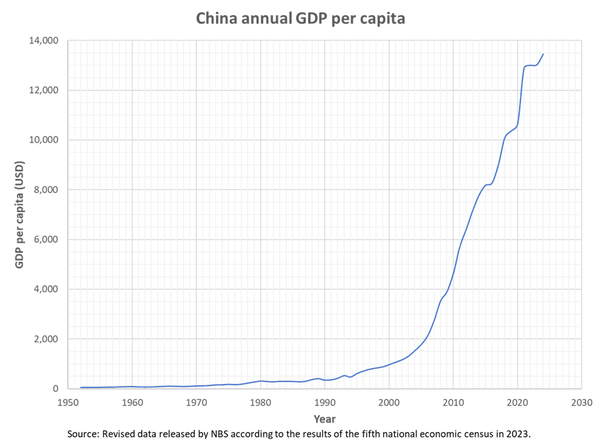

One must also not forget that this fastest rate of national literacy also specifically post-dates the Mao Zedong era and the Cultural Revolution (and its policies which effectively stunted university education for the better part of a decade, amongst other things), and coincides with China’s opening up under Deng Xiaoping’s leadership. Again, well after the promulgation of Simplified Characters. When you overlay the above statistics against China’s GDP per capita since 1952, you get a similar observation whereby the fastest GDP per capita growth occurred after the 1980’s:

From this perspective, my opinion is that credit for China’s mercurial rise in national literacy rates from the last two decades of the 20th century should rightly be accorded to the implementation of its national education policies mandating education to a minimum acceptable level across the populace — and not simply attributing it to the simplification of a few hundred Chinese characters. To put it another way, I believe that China’s educational reforms across the 1980’s would have borne the same positive fruit even without having to go through the prior character simplification process.

So much for timelines and leadership policies. I would now like to pivot over to the concept of literacy itself.

At its most basic level, literacy is defined as “the ability to read and write”. Su (2022) in the same paper above, also quotes the PRC’s Ministry of Education:

“The definition of non-illiterate by the State Council and the Ministry of Education of China is: Farmers can learn 1,500 Chinese characters; employees of enterprises and institutions, and urban residents can learn 2,000 Chinese characters; every person can read newspapers and articles and can do simple calculation; every person can do simple practical writing.”

Here is where I see a problem, with reference to certain classes of the promulgated Simplified characters:

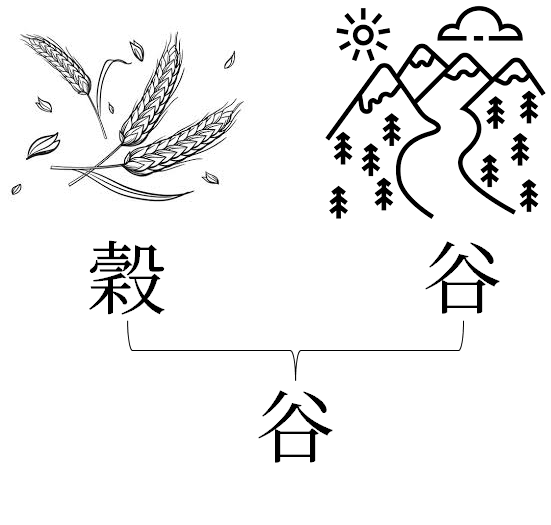

穀 / 谷 belong to the class of character simplification where two (2) distinct words that happen to be homophones are merged into a single character. Here, the words for millet (穀) and valley (谷) — two obviously different words — have been merged into a single character, on the basis that they are both pronounced the same: gǔ.

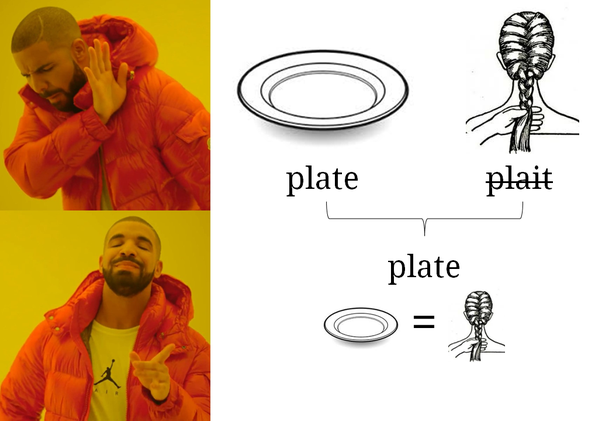

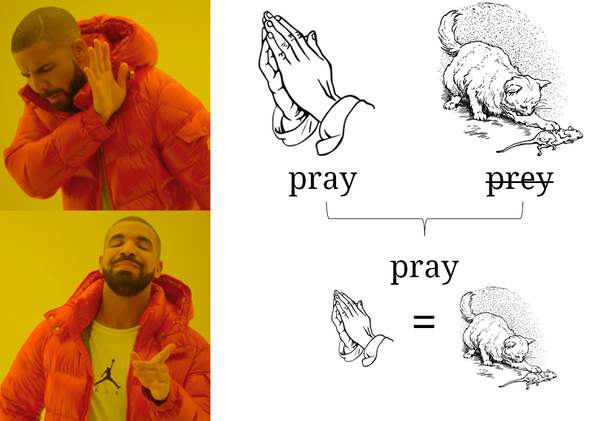

Consider this one example in the light of the Ministry of Education’s definition of literacy: The cut-off for determining literacy for a hypothetical farmer was 1,500 characters per the guideline. Let us suppose that following an assessment, he came out one character short of that cut-off because he did not know the word 穀 millet (coincidentally, this word happens to resonate with his livelihood as a farmer). Is the way to close his gap in literacy to take some other same-sounding word 谷 that has less strokes and make it millet for him? Because to justify that as a means to an end in “raising literacy” is, to use an example in the English language, no different from doing this:

Or this:

If we flipped the scenario around, and suggest that English be simplified this way in the name of “raising literacy”, would you find it acceptable? Dumbing down spellings to the point where you tell new learners that the word for “communicating with a deity” is the same as “one animal killing another”? I mean, the English language is already messed-up enough with multiple definitions for the word “set” (spanning nouns, verbs, and adjectives — go look it up yourself), so I don’t see why Chinese has to emulate the same madness. We are already seeing the widespread English brain-rot today, where self-professed English speakers from the U.S. and Australia cannot even differentiate between there vs. they’re, where vs. were, etc.

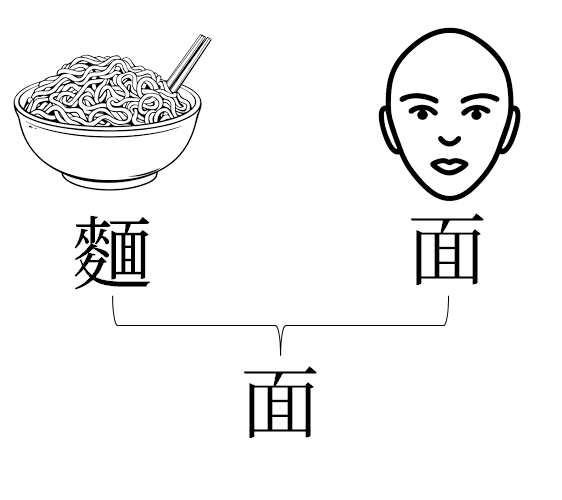

Same goes with this one:

This one really annoys me. There is already a simplified form for the wheat 麥 component, i.e. 麦. Was it therefore so difficult to make the corresponding simplified form of 麵 as 麺, in order to maintain structural and semantic consistency? I mean, Japanese kanji uses 麺 — looks like they got their heads screwed on right for this one. So, the folks in the Committee for Character Simplification figured that making noodles and face the same character purely on the basis of them being homophones “promotes literacy” – was that it?

Besides, there is a certain logic and genius in Chinese characters. The character 穀 has the 禾 radical embedded within it, giving the semantic meaning of grains. It is tragic that somewhere along the way, some folks decided that character simplification in the name of raising literacy should place a premium on sound over semantics — effectively killing the logical genius embedded within Chinese characters’ literacy powers.

Ditto for 麵 (even if it was written as 麺), where 麥/麦 gives the semantic meaning, and 面 supplements with the phonetic:

Be it English, Chinese or any language, the result of this would be that you achieve “literacy” in a superficial sense, because your “literate” people would be functionally-illiterate. Sure, they can read and pronounce the words — but to what end, when they can’t differentiate plate from plait, or millet from valley in a text?

By the way: Please do not ask me to cite more examples in order to buttress my argument. There are way too many of them. I am only citing a few for brevity, and not because I am cherry-picking. If you are literate in Chinese, you will already know some of the other valid examples out there.

Footnote:

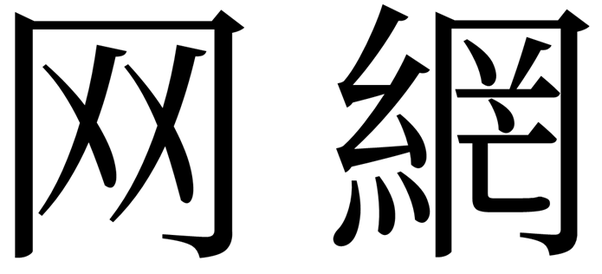

Quorans who read my answers regularly will know that I support Traditional Chinese Characters as standard. But I need to clarify my stance: I do not necessarily support all the current Traditional forms. There are actually some older and simpler forms — some of which were eventually adopted by the PRC’s official Simplified Character set – that I feel should have been the canonical ones in the Traditional set. Most of them are later-developed 形聲 versions of what were originally 象形 or 會意 forms. I will cite two (2) examples:

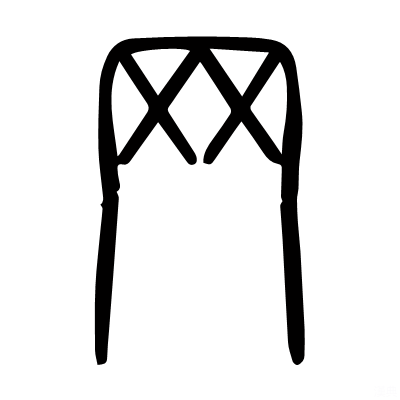

The left-side one is the current Simplified form. The right-side one is the Traditional form. If we trace the etymological origins of this character, long story short is that it originally looked like this:

This is the form as recorded in the《說文解字》character dictionary. It defines the character’s shape as “a cover with criss-crossing lines below — as per a net” (从冂,下象网交文。). It was only later that the character evolved into its semantic-sound (形聲) form, combining the semantic element 糹(silk) with the sound element 罔 -ang. So, 网 came before 網.

And by extension, the shape of 网 can be seen in its radical form 罒 when it appears in characters such as 羅 and 羈. For the record, I actually prefer 网 to 網, for the reason of etymological accuracy.

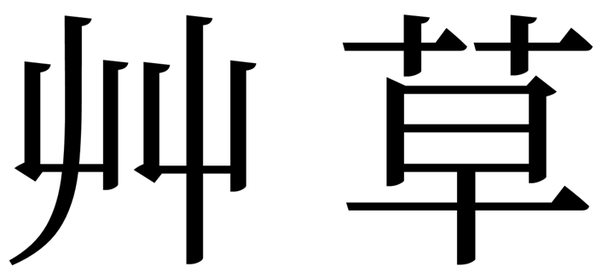

Same goes for this pair:

This one is more controversial, as both Traditional and Simplified character sets use 草, not 艸. However, I contend that it should have stayed as 艸, its etymological clearly coming from the image of two blades of grass. Even its radical form, i.e. 艹, bears resemblance to it. I never understood why it had to be changed from a 象形 character into a 形聲 character — truly redundant when you consider that 草 is simply its original semantic component 艸 compressed into 艹, and with the phonetic component 早 -ao added to it.

In closing: You do not “raise literacy” by dumbing down a language to suit the masses. You raise literacy via correct policies and good governance, and by investing time and resources to teach the language properly to the masses. I am convinced that the nine-year compulsory education would have been no less effective without character simplification — in fact, it would have produced far more literate people who can properly differentiate between the words for millet and valley the way their forefathers could.

China has far better literacy rates today compared to a century ago, because she has far better governance, economic standing and education standards. It is not because 書 has 10 strokes while 书 has only 4. Chinese do not automatically become more “literate” when the mane and legs of the horse are simplified, turning 馬 to 马.

And please: I’m not saying Chinese people today are illiterate. I’m just saying that character simplification was an unnecessary and irrelevant step to achieving China’s high literacy rates today.