I am not a scholar, but on this question I am 100% certain that I am correct.

First of all, I am Chinese, deeply familiar with Chinese characters. Secondly, I am also a calligraphy enthusiast—I have truly written tens of thousands of characters with a brush.

Before the invention of paper, and after the oracle bone script, most writing materials in ancient times were bamboo slips. This period may have lasted for about 2,000 years, and at least 50% of China’s most important classics were first written on bamboo slips.

(These are truly national treasures among China’s cultural relics, precisely because bamboo is highly prone to decay. As of 2025, only 300,000 bamboo slips have been unearthed across the entire country. These slips have been preserved under extremely specific conditions—such as in arid regions or oxygen-deficient tombs. The oldest discovered so far dates back to 335 BCE, and even earlier examples have yet to be found… It’s genuinely a great pity.)

Although I have never written on bamboo slips, I can perfectly imagine the feel of writing on them.

In such a case, only vertical writing is reasonable. Why? Let me explain!

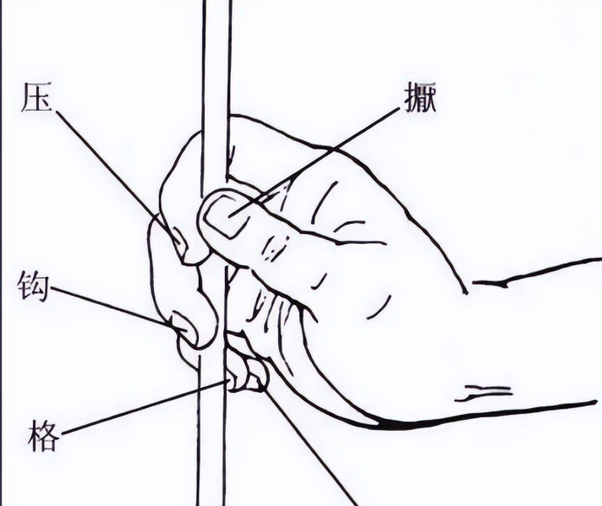

First, above is the common way of holding a brush.

Second, in printed typefaces, the horizontal strokes are strictly level.

But in actual handwriting, no one writes like that—it would look extremely awkward.

Why? Because it goes against ergonomics.

When writing a horizontal stroke, in reality the brush follows the natural structure of the right wrist, drawing a slightly upward curve toward the top right, as shown in the illustration:

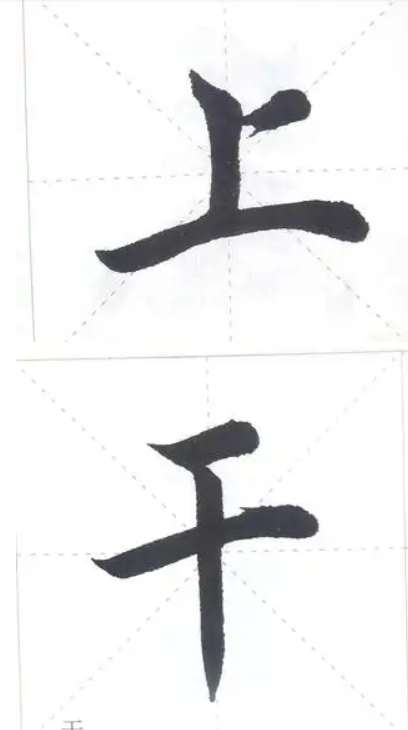

Therefore, in authentic handwritten Chinese, horizontal strokes are all tilted upward by about 15 degrees.

(For example, see these two characters in handwriting.)

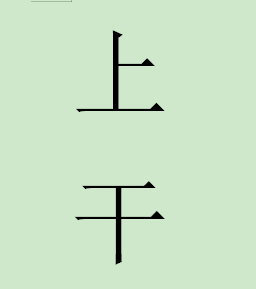

(The above is printed type. Notice—the horizontal strokes in print are absolutely level. You may also notice that printed horizontals are thinner than verticals, and the ends of horizontals often have a small triangular shape. This is a vestige of the aesthetic of handwritten calligraphy, but not central to this discussion.)

So, a key feature of handwritten Chinese is this: the horizontals are not level, but slanted upward to the right (since the vast majority of people are right-handed), while the verticals remain quite straight. This is determined by the structure of the wrist.

Now, let’s consider the writing medium at the time: bamboo slips.

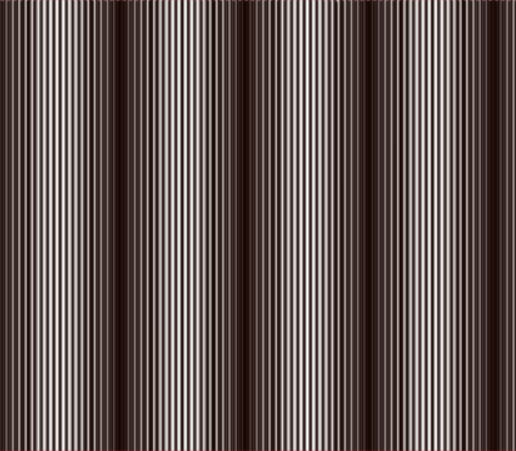

(I didn’t find an image of bamboo slips, so here is a moire pattern illustration instead, but the principle is similar.)

Notice: the texture of bamboo slips runs vertically.

On such a surface, which naturally has countless tiny grooves, writing along the groove direction—i.e., writing vertical strokes—is very easy.

If one were to write horizontally (left to right instead of top to bottom), writing vertical strokes across the grooves is somewhat difficult, though still manageable.

But horizontal strokes are another story…

If you write left to right, those slanted horizontals will cause the brush tip to be pulled along the fine horizontal grooves, resulting in jagged, saw-tooth-like strokes—both laborious and unsightly.

I am no expert, but as a calligraphy enthusiast who has written countless characters with a brush, if I were to write on bamboo slips, I would unhesitatingly choose vertical writing.

For non-Chinese, the beauty of calligraphy can indeed be hard to understand.

My own skill is very low, but I often find myself completely absorbed by it.

Of course, my ability is limited—I can only grasp a small part of its efficiency.

Yet even that is enough to intoxicate me.

For example: a brush is made of animal hair. After writing a few characters, the hairs may become disordered and need to be realigned by rubbing against the inkstone:

But calligraphy masters often adjust the brush while writing itself, using the act of writing to restore the tip, without having to stop and realign after every few characters!

This effortless control is irresistible to me—it feels as satisfying as watching a lathe cutting metal, utterly smooth.

Another example:

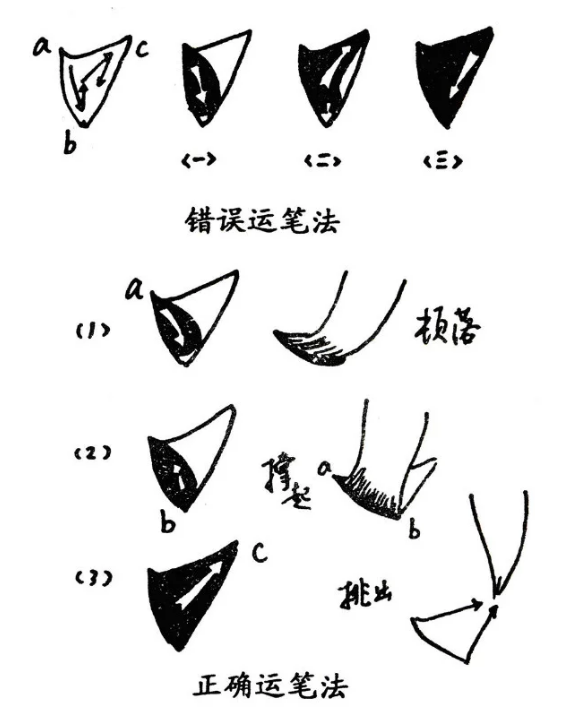

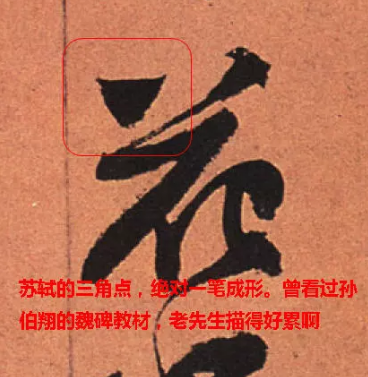

This triangular form is very common in calligraphy.

(The first line is wrong—this person spent a lot of time trying to “trace” the shape of the ancient calligrapher’s stroke. The correct way is shown in the last three diagrams: press down, lift, and contract, all completed in an instant. But it requires extremely high control.)

(Evidence)

Such efficient writing produces a strong sense of joy.

It’s a bit like what I said earlier about a lathe, or like watching top-level Tetris play.

Our genes predispose us to enjoy efficiency—those who didn’t were eliminated in the harsh process of evolution.

Calligraphy is no exception.

~~~

What I said is merely the reflections of a beginner, utterly incapable of summarizing this great art. Yet even these reflections are enough to fascinate me.

Take the Tetris example I mentioned earlier—you might have seen top players who, instead of clearing lines immediately, keep spectators on edge by letting the blocks pile up. Then, in the end, they clear a dozen or even dozens of lines in a row, leaving you exhilarated, right?

Similarly, there are masters in calligraphy who intentionally create precarious situations, making you think the structure is beyond redemption, only to turn it around with brilliant techniques that leave you in awe. See, humans are fundamentally connected in their passions and appreciations!